Pushed by the recent flurry of articles on Apollo and the history of space flight, I went and watched for the millionth time 2001: A Space Odyssey. Every time I go back to Kubrick’s masterpiece, there’s always something new to find and notice. This is what caught my eyes this time.

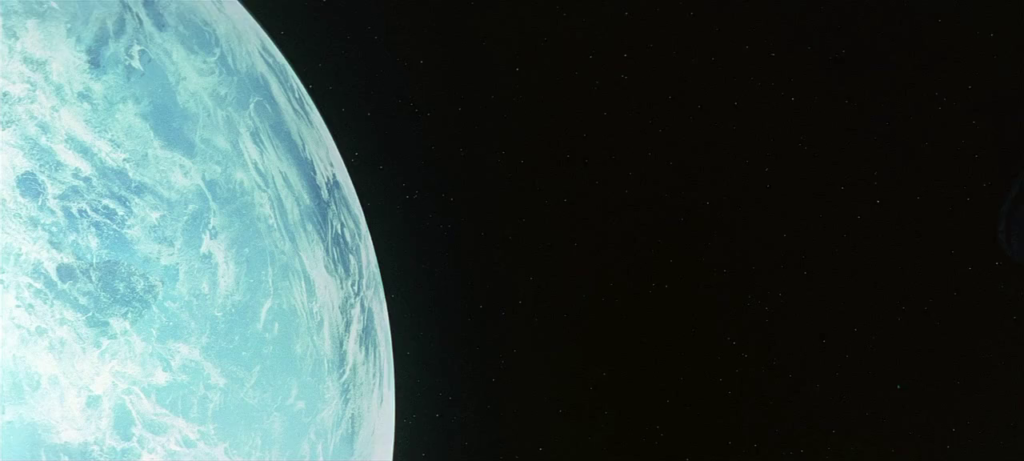

Earth seen from space is a lot less accurate than the Moon or to a certain degree even Jupiter!

Fascinating to think that during the production of 2001 Kubrick might have had better access to Moon or Jupiter telescope images than Earth. It was still a few years before Blue Marble would be taken: Earth looks like an artist rendition of how they imagined it to appear from orbit.

During the flight to the Space Station, a flight attendant turns off the In-flight entertainment for Heywood Floyd while he’s taking a nap.

It looks like a very simple gesture, almost motherly, yet it made me think of our very contemporary struggles with energy consumption and resource optimization. It might be an overreading since the cabin seems to be unnecessarily illuminated, but who knows. Maybe Kubrick was aware of the preciousness of energy in space.

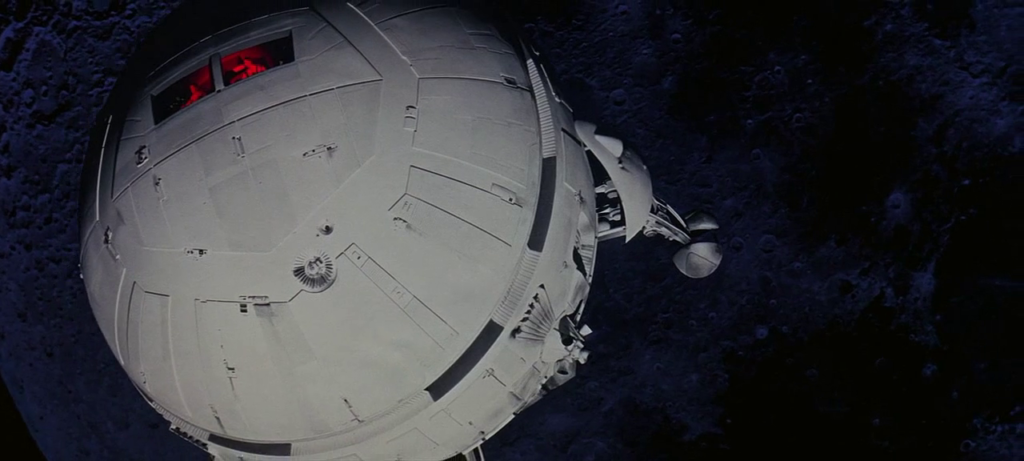

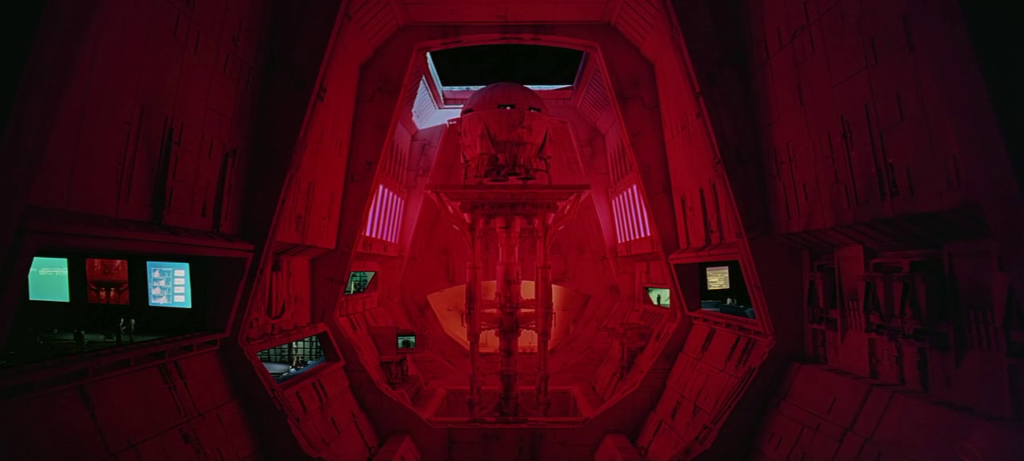

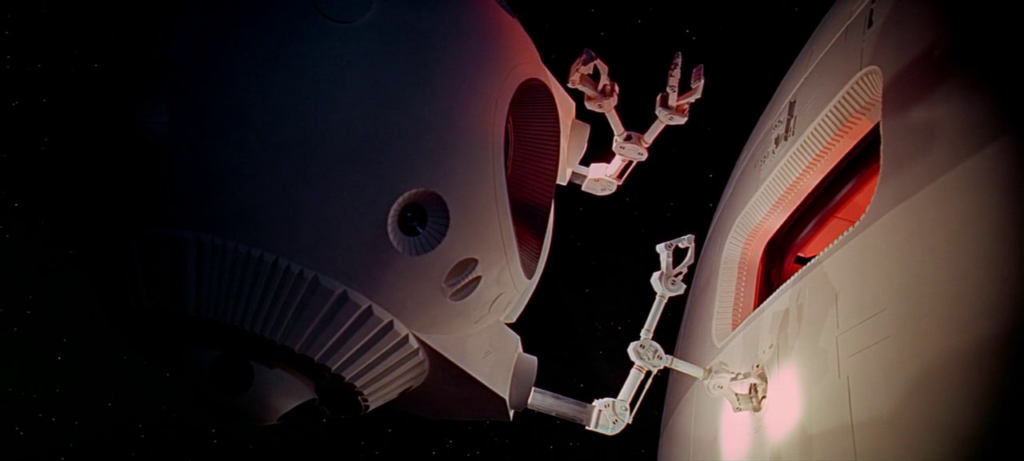

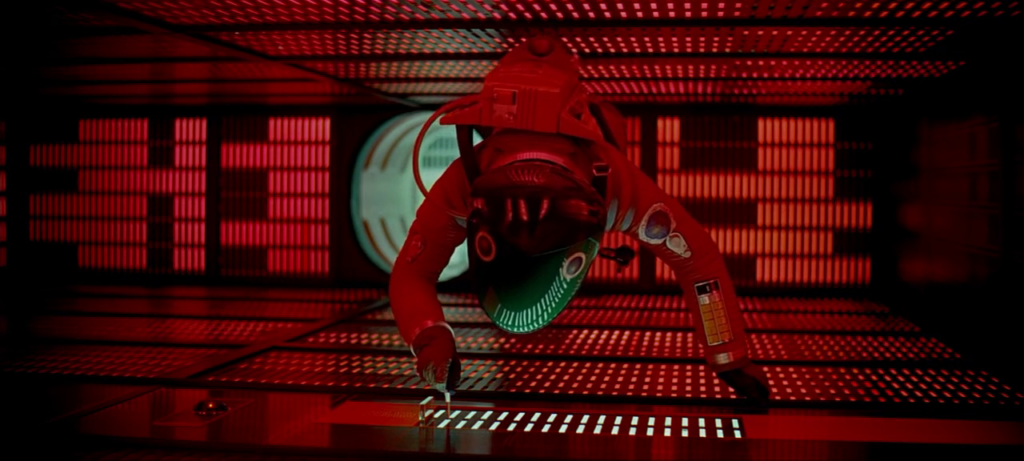

Use of the color red for the innards of spacecraft.

It’s possible that Kubrick was trying to simulate night vision (rod cells are insensitive to red light), which is common for several nocturnal applications from cockpits to star-gazing screens, but it’s equally possible to think about the symbolic meaning of the color red in this case. The redness inside those vessels is similar to the redness inside the vessel of our minds, blood. One of the most important characters in the movie is a computer which is effectively the mind of a spacecraft: it looks like Kubrick is warming us to the notion that those man-made machines are not too different from ourselves.

The sadness of looking at the Clavius cover up story in 2019.

In the future imagined by Clarke and Kubrick, people at the top invent a cover up story for the sake of adequately preparing the population towards a cultural shock. The key concept here is that the lie is benign and with the intention of protection. Now compare that with the present situation: nothing epitomizes the closing of this decade quite like the surge of conspiracy theories and “fake-news”. For every piece on the 50th anniversary of the Moon landing, there is seemingly another giving fuel or anyhow talking about the so called “Moon landing hoax”. The worst part is that there doesn’t seem to be a specific direction from where these stories originate. They seem to be coming from a cross-section of the human species and mostly seem geared towards destruction (status quo, world order, etc.) instead of construction. I, for one, long for the time when conspiracies where real, well architected and coming from a far-looking top.

The question on whether machines can have feelings is immediately dismissed.

A BBC journalist asks Frank Poole: “Do you believe that HAL has genuine emotions?”, to which his response is: “Oh, yes. Well, he acts like he has genuine emotions. Of course, he’s programmed that way to make it easier for us to talk to him. But, as to whether or not he has real feelings… is something I don’t think anyone can truthfully answer.” I find it mesmerizing that in what is probably one of the most philosophical movies ever made, this question is explicitly posed and dismissed in 3 seconds. My understanding is that Clarke was familiar with the Turing test and with the emerging philosophy of artificial intelligence, and understood that much of these questions stop making sense when treated in human terms. In the words of E. W. Dijkstra: “the question of whether Machines Can Think… is about as relevant as the question of whether Submarines Can Swim”.

A bicycle built for two

In what has been described as the most poignant scene of the movie, HAL 9000 slowly loses his “consciousness” as David Bowman unscrews its memory banks. The last thing we hear from HAL is its singing of a “Bicycle built for two” while its voice slows down. I was already aware that this was a reference to the IBM 7094 speech synthesis demo, one of the earliest of this technology. But only now I realized how much the first thing of its kind always ends up influencing and being referenced by what follows. Other examples: the Utah teapot, which is an in-joke in countless 3D productions; or outside academia, the overwhelming amount of DeepDream generated images that look like dogs (because Google trained its model on a subset of the ImageNet database which contained “fine-grained classification of 120 dog sub-classes”). Perhaps the only thing that saved Lenna from becoming an oft-quoted meme was the sexist controversy surrounding the image. I am curious to see what will become the standard test for technologies that do not even exist today.

The unbearable lightness of mistakes, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Error.

Kubrick was a genius. And a meticulous one. He took his time to film the way he wanted and often shot the same scene over a hundred times. He wanted everything to be perfect. And essentially, that’s what people saw watching his movies. A friend who happens to be a director once confessed me to dislike Kubrick’s oeuvre because, in his words, “it’s too perfect”. I suppose it can become daunting, if you work in that industry, to compare yourself to Kubrick’s level of quality. Yet, perfect it isn’t. If you watch 2001: A Space Odyssey as many times as I did, the imperfections start surfacing. Wrong lights, rubber bones, continuity errors, very obvious non-Russian actors, weird cuts… the list goes on. It’s impossible to think that Kubrick was not aware of at least some of these issues while he was filming the Proverbial “Really Good” Science-Fiction Movie. But it’s a positive message for all of us. If a genius like Kubrick could cut himself some slack, then perhaps we on planet Earth can do it too.

Post a Comment through Mastodon

If you have a Mastodon account, .