A number of things happened in the past few months that got me revisiting the early gaming scene, the period spanning from the early 80s to early 90s.

First off, Thimbleweed Park™ was released and with it, many gamers (young and not so young) flooded the interwebs with enthusiasm for the game, which is essentially the ultimate homage to point-and-click adventures. I played the game and thought it was excellent: even if it comes as a bit too self-referential, I hope there will be similar efforts to revive the genre in the future.

The game got me interested in the work of Mark Ferrari, one of the best 8-bit artists out there. With his ingenuity, technical intuitions and mastery of light, he brings entire fantasy worlds to life. He was involved in the making of background artworks for several important Lucasfilm games, plus a million other things you can see on his website.

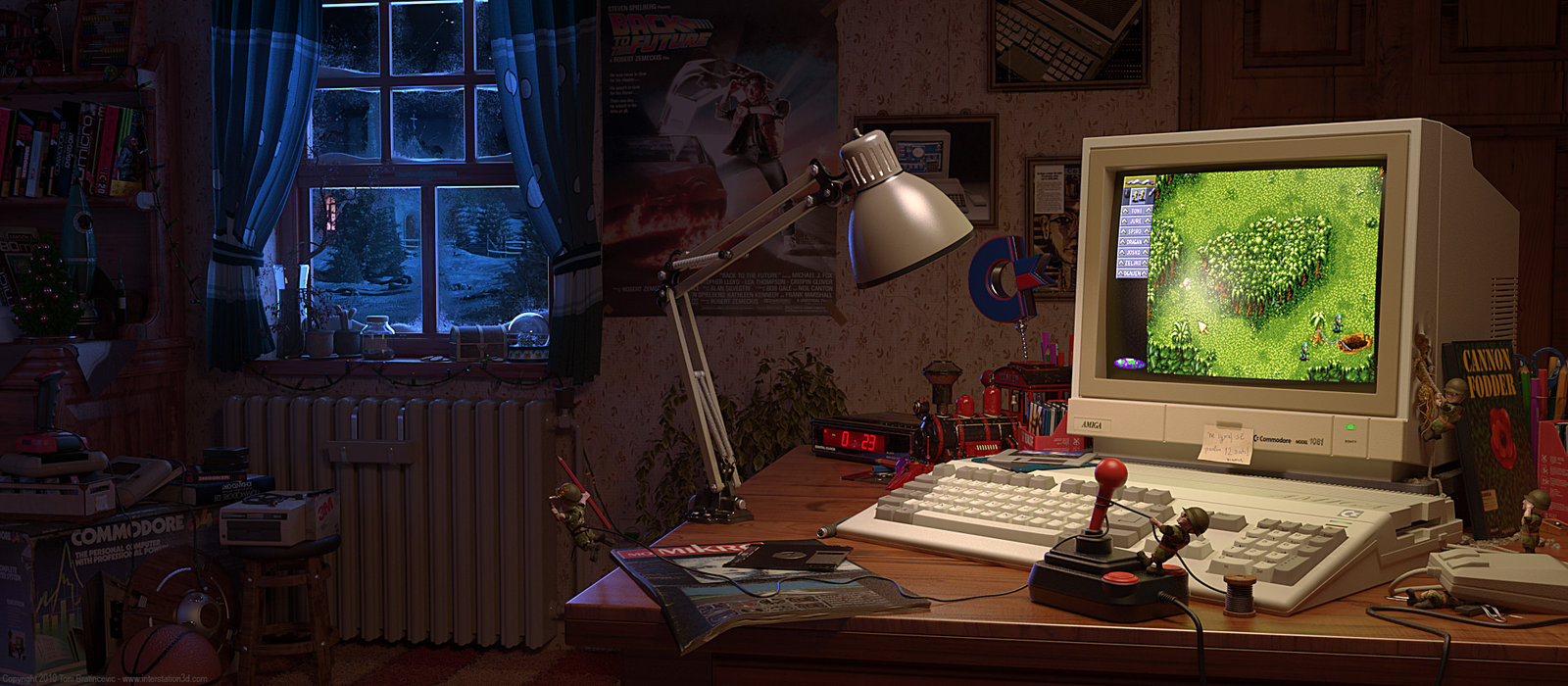

The last thing that happened was a lucky trip to Japan. There, lost in the shady streets of Akihabara, I acquired a PSP for $30 and turned it into a great portable retro gaming device. Any emulator running software/games from the beginning of time to ~1995 works amazingly well on this light handheld.

And there, as I was being entertained once again on titles from the C64, NES, GB, SNES plus many more games emulated on the ScummVM, it dawned on me that, while there is certainly a nostalgic component to the retro-gaming fever, there is a lot more to be found. It’s a combination of freedom and restrictions that enabled so much creativity in the early gaming scene.

The early video game industry was a gold rush. The appeal of a new opportunity made it so that many gaming firms in the 80s were born as the effort of one or two computer programmers working from home and trying something new. The budget for creating a game was considerably smaller, so there were more individuals closer to the creative process, which in turn generated lots of independence. The result: a Cambrian explosion of video game genres and hundreds of crazy experiments. The history of early video games is littered with stories of programmers that came up with ground breaking results because of their freedom from corporate structures.

It’s a known psychological phenomenon that creativity arises in constrained contexts. Limitations in early video games were subject to both internal and external factors. Externally, video games would be constrained by limited hardware and software libraries of the era. An entire form of art known as demoscene arose from exploiting these limitations and is today still alive and kicking, artificially maintaining those technical constraints in the same way Haiku poets revere the traditional Japanese meter. Internally, video games began to segment very early into different styles or genres. Some of these narrative methods were extremely successful and they multiplied. Others were too strange for this world and disappeared. Who knows, if pieces such as Moondust (Jaron Lanier, 1983) had become more successful, perhaps it would have been easier to shake away the word “games” from “video games”.

But that did not happen. And it seems like a lot of the criticism towards video games as a form of expression comes from this cursed, playful term, which prevents it from being taken seriously. Nomen-Omen. Video games are still seen as a mere form of entertainment and the debate on whether or not they are a legitimate form of Art is far from being settled.

I for one feel that several video games, especially from, but not limited to the early days, tick all the checkboxes of a form of Art. They give a sense of timelessness; they are life changing; they can be transcendent; ultimately, they are beautiful. The well-articulated criticism of Moriarty towards video games as an art form reminds me of the cynicism that some artists display, after working too close to a medium for many years. Mastering a technique can liberate the fantasy, but can also kill some of the mystery that lies in the process of creation.

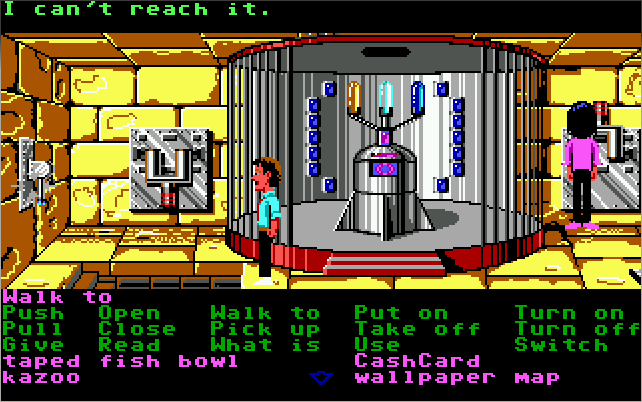

Several of the video games that I would consider works of art are graphic adventures. Just like a good book or a great movie, you can get back to them after a few years and find a lot more to discover. In the case of books and movies, the only thing that has changed in time is yourself and the historical context in which you experience the oeuvre. In the case of adventure games, you can discover so many new things on a second play. I must have played Monkey Island a dozen times and still enjoy it enormously. These games enjoy a nonlinearity that is barely rivaled to these days. True, we do have amazing Open Worlds today. Driving around in GTA 5 gives an amazing illusion of openness, but enter any Mission and you will suddenly feel on a linear track with only two outcomes: failure or success. The latest Tomb Raider or Uncharted may well enjoy the best graphics we got, but in terms of true freedom of action, they don’t feel too different from laserdisc games like Dragon’s Lair, limited to exactly one correct move at any point in the game.

The nonlinearity of early graphic adventure games had its share of problems. Debugging every possible state was a mess and it was not uncommon to reach an unwinnable state that would force players to start over. But in general, it did offer many storytelling possibilities. Games in which you can explore a conversation tree go even further, giving players the thrill of role-playing.

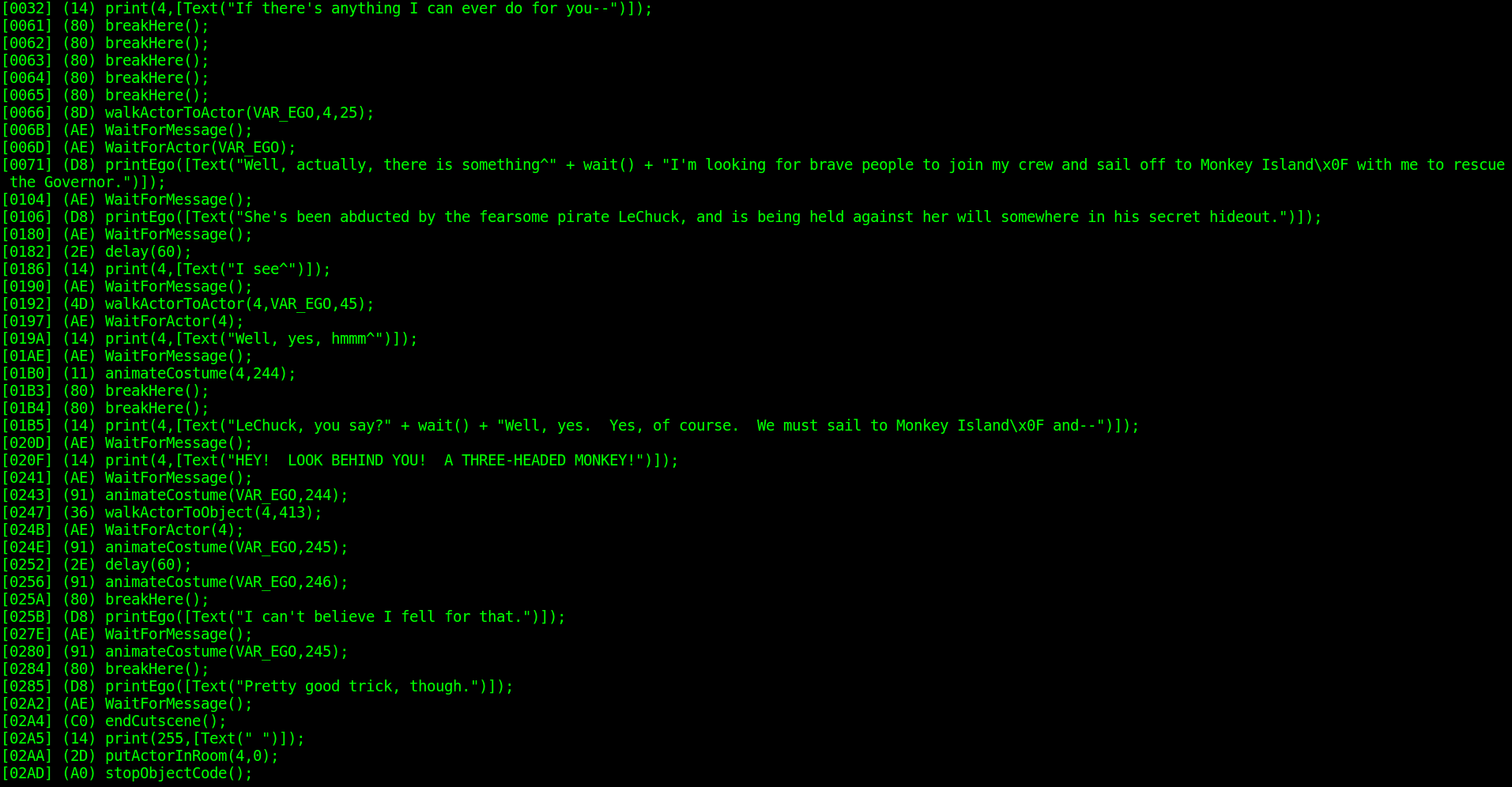

One thing that is not limited to graphic adventures is the joy of entering into the mind of the Author by breaking the game open. No other form of art allows you to get so close to the thought process that went into its creation. By x-raying a video game you see not only the scenarios that were considered by the game makers, but you can also find remains of elements that could have been, but were abandoned in the making. Far more exciting than a lost alternate ending or a director’s commentary.

The practice of playing a video game to its extremes, to the point of bending it upside down and breaking its own rules, is not specific to ancient games, but it’s impressive to see how vital some communities dedicated to 20 years old games are. Take for instance TASVideos, a website dedicated to Tool-Assisted Superplays – when human skills are just not enough. In one of the videos published, Super Mario World is being played by one of such tools. In less than a minute of play, “the fabric of the game’s reality comes apart at the seams for a few seconds before inexplicably transitioning to Mario-themed versions of Pong and Snake”. The game has been opened and studied so thoroughly that it becomes itself a tool for the creation of something new. I think any artist would love to see that happening with their own work.

It’s remarkable how video games sit in this weird limbo in which millions of us play them daily and yet they are still an awkward topic to bring up at social dinners.

Not sure any art form ever suffered from this, and if so if the transition period to something taken seriously by any grown-up was this long.

I am loving (recent) games that make me feel as part of a real cinematic experience, albeit one where I am the main character. Sometimes they might be limited in terms of choice, yes, but the sense of being that character just overrides every other feeling. And when the story and the characters are deep, that’s everything you need.

The comparison with movies is illuminating. Even when we take for granted that Cinema can be an art form, its acceptance in a formal setting is incredibly low. How many countries integrate into their school program a class on the fundaments of cinema? I would have loved even just a short course on the subject. It’s the old problem of disconnect between the educational system and the real world.