Imagine one day radio telescopes around the world receiving a mysterious message from Mars. What does it contain? How to make sense of a message coming from outer space? These questions and the general premise describe A Sign In Space in a nutshell.

Daniela de Paulis conceived this project over the span of several years. The team she formed comprises over 70 individuals, including scientists, intellectuals, and artists, other than key collaborations with the SETI Institute, the European Space Agency, the Green Bank Observatory and INAF, the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics. I had the privilege of joining the project only in November ’22. However, I could make a meaningful contribution as I was part of the message team, along with Daniela and astronomer Roy Smits.

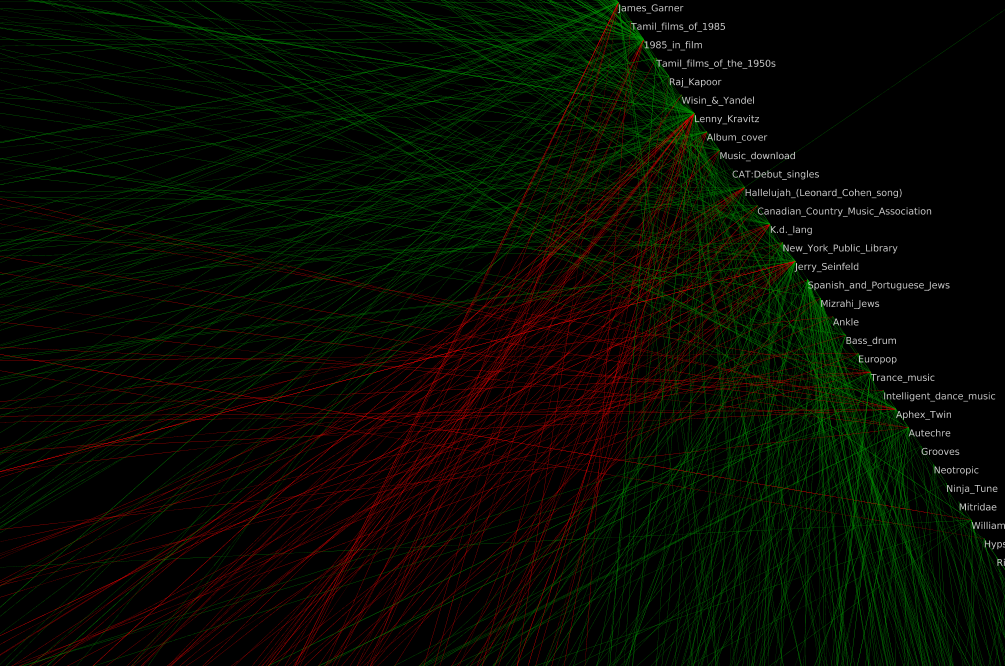

In a live performance on May 24th, 2023 the message that was loaded on the Trace Gas Orbiter, a spacecraft orbiting Mars, was beamed back to Earth. Since then, a community of space enthusiasts on Discord have been trying to make sense of the message. As of early 2024, the message is considered by the community to contain a header, body, and footer. The body, predominantly rendered as a 256×256 image, has become popularized as “the starmap”.

I won’t reveal much else until the community finishes interpreting the message. However, I can share that working on this project was an immensely humbling experience for me. The challenge of putting oneself in the shoes of another sentient entity in the universe is mind-bending to say the least. Having worked together with so many talented people made up for some of that sense of insurmountability of the task. A Sign In Space was for me also a wonderful excuse to review some of the scientific work done before us, like the Arecibo message, the Voyager Golden Record (and more generally the work of Carl Sagan), and discovering much more, like the great project by Jordi Portell.

Visit the website of the project or the discord channel for more information on the status.

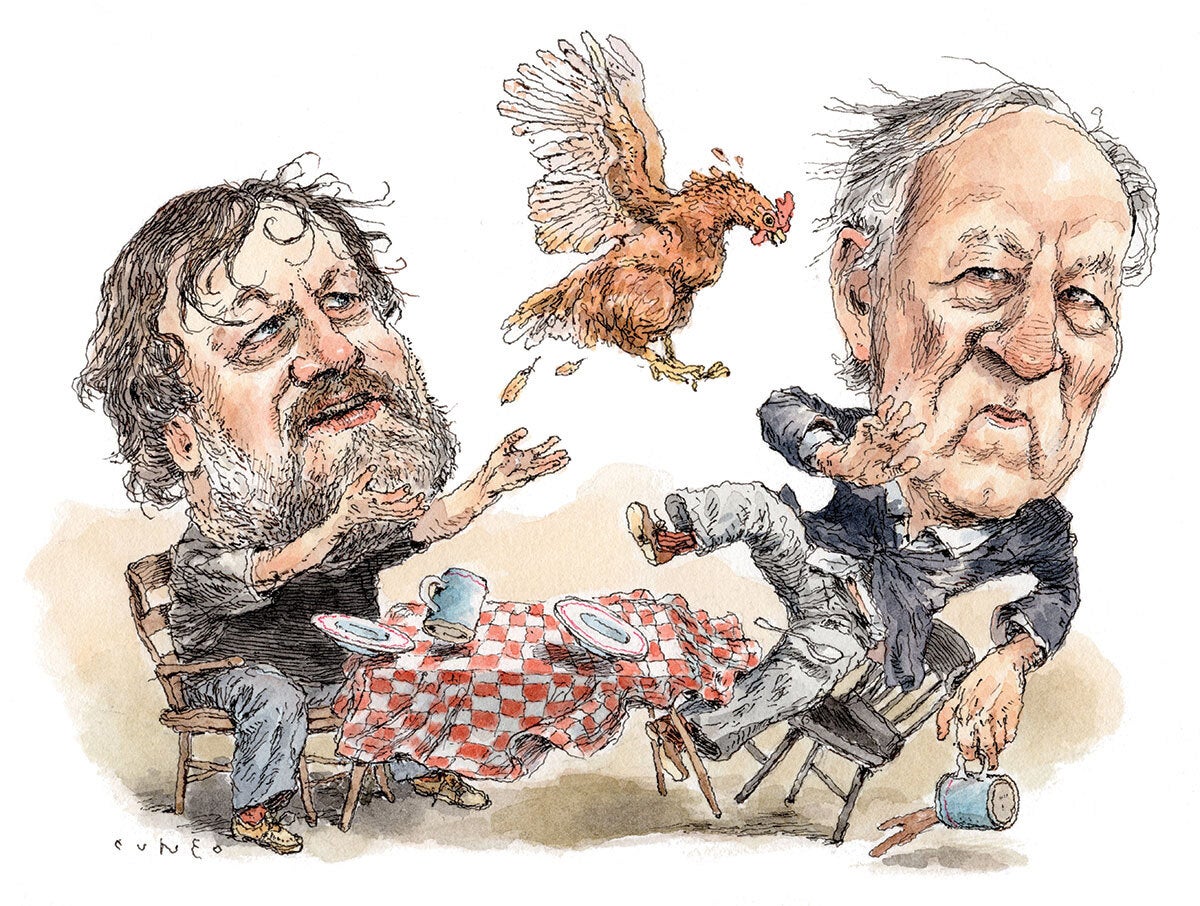

(Illustration courtesy of John Cuneo)

(Illustration courtesy of John Cuneo)